| Membership | Price (+HST) |

|---|---|

| Single | $85/year |

| Single Plus | $120/year |

| Family | $130/year |

| Family Plus | $175/year |

| Contributing | $300/year |

| Supporting | $600/year |

| Sustaining | $1,000/year |

| Benefactor's Circle | $2,500/year |

| Director's Circle | $5,000/year |

| President's Circle | $10,000/year |

Transitioning from Fall to Winter in Nature

By Dr. David Galbraith, Head of Science, Royal Botanical Gardens

One of the delights of living in Canada is the changing seasons. While not restricted to Canada alone, of course, our seasonality and the ever-changing environment around us means we always have something to look forward to. Spring brings the balmy days of summer, and summer’s biological luxuriance leads us into fall. Fall’s the time when nature prepares for the harshest period, winter, and winter leads us in relatively short order back to spring again.

For animals and plants, winter’s chill is only part of the story. Cold weather certainly slows down many organisms that depend on the warmth of their surroundings for their metabolic rates. Frogs, salamanders, snakes, and turtles start seeking out hiding places as the temperature cools off. By avoiding exposure to predators that might take advantage of sluggish behaviour, such animals – called ectotherms – have a great strategy. Don’t fight the cold. Avoid it.

Left to right: Red-spotted Newt (Notophthalmus viridescens), Common garter snake (Thamnophis sirtalis), Lion’s mane (Hericium erinaceus)

Finding snug places, often underground, allows many small animals to avoid predators. Such places may not freeze, avoiding another risk. For animals, cold itself can precipitate serious tissue damage. As water solidifies it can form sharp crystals that grow and puncture delicate cell walls. When that happens to us, it’s called frostbite, and it can be debilitating or fatal for animals too.

Another way of looking at winter is to consider the availability of water. When the temperature is below freezing, liquid water (kind of by definition) is hard to find. While it may seem strange to think about winter as a dry period, especially when we’re surrounded by mounds of snow, it can in fact be exceedingly dry. It’s that dry aspect of winter that brings on the condition that gives autumn its other name – fall.

In the dry air of wintertime, water loss is a real problem. To limit water loss, deciduous trees drop their leaves in fall before the driest period begins. Leaves tend to be efficient at photosynthesis but have large surface areas and are thus a vulnerability for drying out. When a plant drops its leaves, it also means it doesn’t have to invest in repairing leaf tissues that might be damaged by freezing. It’s easier, it seems, to just cut the losses and grow whole new leaves in spring.

As the autumn proceeds into winter, we can watch these shifts taking place all around us. Leaves begin turning colour as the veins that carry fluids from the branches out to the leaves start to constrict. This is triggered by shorter daylight hours. A special layer of cork cells grow at the base of each leaf, gradually shutting off the supplies the leaves need to function. As green chlorophyll, responsible for photosynthesis, starts to degrade, it become colourless, revealing a variety of yellow and orange-coloured compounds already in the leaves. Some compounds, especially red anthocyanins, are then produced in the leaves as chlorophyll declines. The blaze of the deciduous forest in fall is multilayered and short-lived.

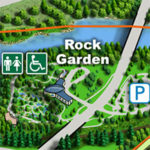

Left to right: Hendrie Valley, Rock Garden, Rock Garden, Hendrie Park

Just why these reddish anthocyanins are produced as photosynthesis is shutting down is not entirely clear. One interesting idea is that in species like maples, the red anthocyanins are allelopathic. When they build up on the ground they inhibit the growth of saplings of other species. Another idea is that the bright colours are a result of coevolution. The colours may be a signal to other species such as birds, or might help reveal herbivores that would then be more vulnerable to predators. Yet another suggestion is that the coloured compounds allow the tree to re-absorb remaining nutrients from the leaves just before they fall. Whatever the explanation, those red colours are costly to make. The colours of fall are indeed transient, and also may be in flux because of climate change. One effect of climate change already being seen is a shorter fall period in temperate countries, possibly linked to higher CO2 levels.

So watch the fall spectacle and brace yourself for winter, which brings a whole new range of sensory delights and biological adaptations. You’re not just watching colourful leaves do their thing. You’re seeing all of nature turning in synchrony with the seasons.

More from the RBG Blog

Check out RBG’s blog for announcements, articles, and more from Canada’s largest botanical garden.

Want to be sure you hear first? Sign up for our weekly e-newsletter to hear about upcoming events, weekend activities, articles, and more!